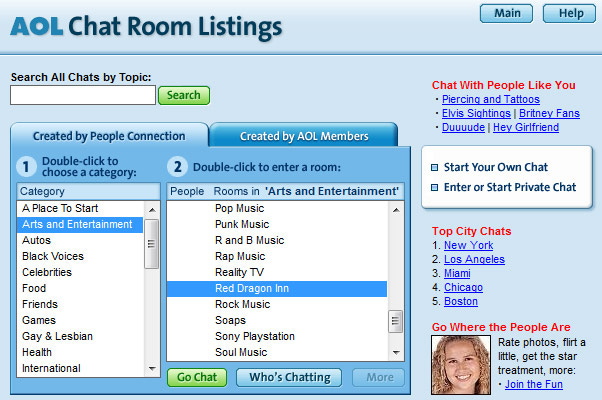

In the early 2000s—precocious but barely literate—I logged onto America Online, entered a chatroom, and observed a funny conversation.

It read something like this:

Username_1: *pulls out my wand* WINGARDIUM LEVIOSA! Wait… why isn’t my wand working?!

OnlineHost: Username_3 has entered The Tavern

Username_2: ((shoving Username_1 aside))

Username_3: OOC: wait… …